Market research is the first step in government acquisition and often favors established contractors and encumbents.

Challenge

Market research is an important part of competitive procurement and is intended to save money and ensure integrity. As a requirement of the Federal Acquisition Regulation, it receives just enough attention to check the box. Buyers believed an electronic request for information (RFI) system would make the process more efficient and also serve as a single source of truth. Vendors did not want to manage another online profile or learn a new system.

When I joined Ridgewood in 2017, an early version of RFIQ had been delivered as development continued. I was tasked with improving the user flow and simplifying the UI. Before I could begin my work, I needed to understand market research in government purchasing and the delta between how it was intended and the customer process. It should be noted that registering and responding to requests as a vendor accounted for > 90% of support tickets.

Process

After building an understanding of FAR Part 10, which stipulates market research, we began talking with everyone from buyers and contract officers to business development and capture management professionals. One thing became clear — users on the vendor side work “closest to the deal” and opportunities in their infancy were not enough of an incentive to register for and learn a new system. If they did, RFIQ would soon be forgotten and profile information outdated.

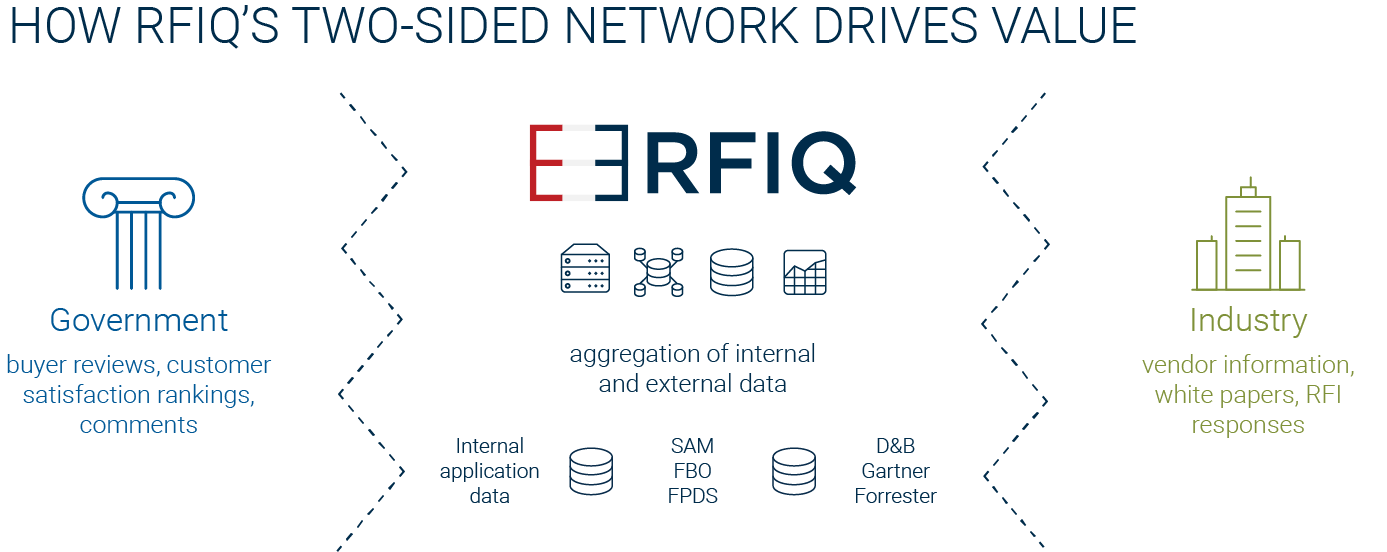

We synthesized that the most effective solution, and in hindsight the most ambitious, was the integration of external data. This effort, referred to internally as the “data factory”, became the focus of the team’s work for the next eighteen months.

Lists were made of the different sources of contract award data and which bits they collected. Classification codes were mapped to categories. And, with a few API calls, RFIQ built vendor profiles on demand. We envisioned these on-demand vendor profiles working much the same way as business listings in Yelp! or Google Maps — for government users the data was never further away than a search, but was “claimed” when a vendor registers. This led to us presenting to product leadership a landmark pivot in direction for RFIQ.

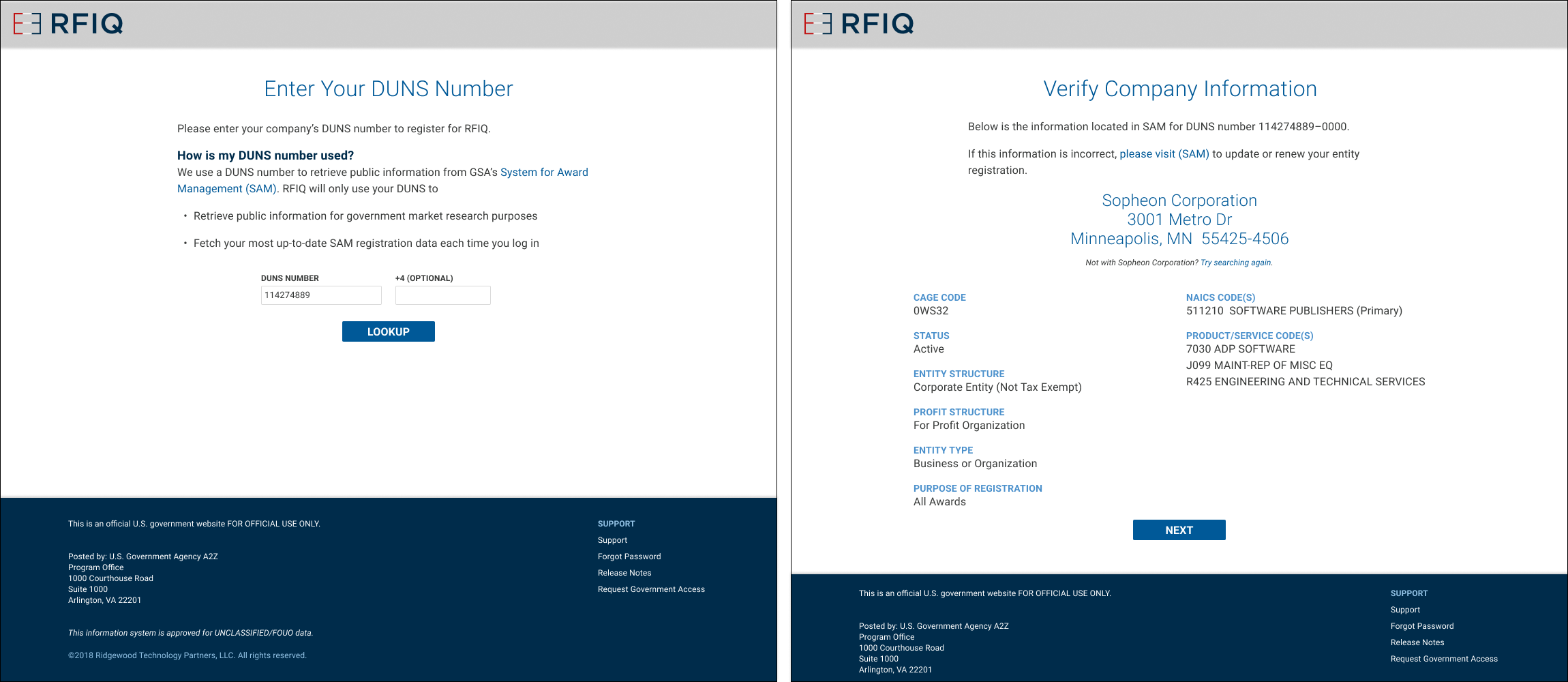

At this point it was clear that design and development of the vendor side of the application had been neglected. A group of us began focusing on a simplified user flow for vendors onboarding and responding to RFIs. We believed the “data factory” could potentially solve our “one more profile” problem. So, what was the least we could require for a vendor to “claim” their profile? We were surprised to learn we needed a single piece of data: the Dun & Bradstreet’s DUNS number.

More importantly, a DUNS number is required for entity registration in the government’s System for Award Management (SAM.gov) — and registration in SAM is required to do business with the government. This was meaningful because we weren’t asking vendors to invest more of their time only to enter the same information into yet another government system.

Vendor registration had been reduced from a multi-page form chock full o’ required fields to a single nine-digit, numeric text string!

There was a silver lining to the data factory — RFIQ’s vendor profiles would always be as current as the most current government procurement data.

Outcome

Third-party data aggregation and the simplification of the vendor UI were both highly successful. Through a process of continuous iteration, RFIQ was transformed from a simple survey tool into a “data factory” providing government buyers a comprehensive procurement information system. RFIs were now a value-add instead of a necessary starting point, saving countless man-hours. Within 30 days of release, the support team reported a 90% decrease in vendor tickets.